Article Written by forbes.com editor.

In 2001, the World Trade Centers fell, and, like many New Yorkers, public relations executive Patrice Tanaka felt her world collapse. Crippled by depression, the tragedy of 9/11 coincided with multiple personal traumas: her husband was terminally ill, the company she had spent decades years building was crumbling around her and she had gained nearly 40 pounds on her petite Asian-American frame. She was coming apart at the seams.

The woman who swept into 60 Fifth Avenue last week was entirely put together. At 60, Tanaka has achieved a level of bliss she calls transformative, and says she lives each day “full-out and fearlessly.” As the chief creative officer of CRT/tanaka, the agency she cofounded in 2005 is award-winning, her career has reached new heights, and Tanaka credits one thing for the incredible turnaround of both her professional and personal lives: competitive ballroom dancing.

In her new memoir, Becoming Ginger Rogers: How Ballroom Dancing Made Me A Happier Woman, Better Partner and Smarter CEO, Tanaka takes readers through her journey from despair to “pure bliss,” and shares the often-surprising life-lessons that she learned along the way. From her first lesson (the fox trot) to her first competition (she won), the experience has been entirely transformative, and Tanaka’s convinced that the 20 million viewers of Dancing With The Stars would experience the same phenomenon—both personally and professionally–if they only let themselves go.

Becoming Ginger Rogers

Here, seven ballroom lessons to help you step up your game in the boardroom.

Leading And Partnering

“I used to be such a solo person,” Tanaka says, “But in dancing, the woman follows, never leads. In learning how to dance, I’ve learned to know when it’s important to be not just a follower, but an active follower in business.”

As the sole owner of a public relations firm, Tanaka was often courted by bigger firms hoping to acquire Patrice Tanaka and Company, but consistently demurred. She was hesitant to relinquish control over her life’s work. But in 2004, she finally demurred and merged with the larger agency Carter Ryley Thomas with a collected $10 million in accounts. As a result, Tanaka stepped down as CEO for the first time in over a decade. “If I hadn’t gotten involved in ballroom dancing, I never would have been open to such a merger,” she says, “It took years of partnering on the dance floor to prove to myself that I could be happy following a leader I had 100% faith in.”

Learning To Let Go

“Sometimes you really have to lose yourself to find your balance,” Tanaka says of learning to let go on the dance floor. When turning, it’s especially important not to hold an ounce of strength back, or your balance can be thrown and you’ll wind up on the floor.

In life, Tanaka says that, while she was striving for success, she had never allowed herself to push past her comfort level. “I wouldn’t speak up if the subject was beyond my expertise,” she says, and the realization that she might be missing her mark by holding back was a revelation. The exhilaration of a perfectly-executed turn now serves as daily inspiration to simply let go, to execute every aspect of her life as “full-out” as she does on the dance floor.

Wearing the Right Costume

When Tanaka took her first dance lesson in the Spring of 2002, her hair was cropped close and she was a devotee of the black power suit. “I was really unhappy and it showed in my appearance,” she recalls. There was no variety, no joy in getting dressed each day.

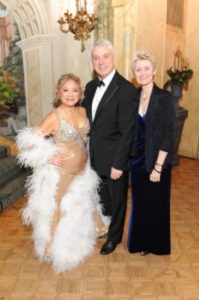

Dancing taught her not only how to express herself physically, but also to dress for the occasion. The Tanaka who visited FORBES to talk up her new book was dressed in beige pants and was bedecked in gold baubles and a swipe of sheer, shimmery eyeshadow. She relishes having costumes made for competitions, and understands the importance of dressing the part more than ever. “I’m a chief creative officer,” she smiles. “And I hope it shows!”

Being Fully Present

“In order to dance well, you must be fully engaged—with your mind, body and spirit,” Tanaka says. “The only safe place to be is in the present—if you think ahead, you’re forced. If you’re a step behind, you fall. If you over think a single mistake, there’s a domino effect and the dance is ruined.”

Tanaka stresses that the notion of “presence” is of paramount importance in the workplace, but so many people—employees and executives alike—overlook it. “Off the dance floor, the metaphor holds,” she says. “So often you’re in meetings and people are physically there, but either mentally or spiritually, they’re checked out.” Only by being fully present can you and those around you perform their best.

Finding Time For You

Prior to following her lifelong dream of learning to dance, Tanaka’s datebook was overloaded with meetings, doctors appointments for her ailing husband, non-profit work and various social commitments. Like many women, she rarely had a moment to herself.

“Ballroom dancing helped me to reschedule myself into my life,” she laughs. For the first time, she was able to find an outlet for her stress each week—and her classes became a total respite from her increasingly frenetic life. By simply taking an hour of personal time, she says she became a far more focused—and committed–leader in the office.

Trading Perfection for The Pursuit of Pleasure

“Professional dancers don’t look at success as a destination,” Tanaka says. “Instead, it’s a journey of continual improvement.” By taking this lesson to heart, Tanaka advises to see each failure as a step towards getting better. “Once you stop striving for that unattainable perfection, you can take pleasure in every accomplishment along the way.”

Case in point? Tanaka points to Sir James Dyson, a friend and an early client. “It took 5,000 failures to create that vacuum,” she says, and nobody call him a failure. “Practice failing, “Tanaka says. “Only by becoming really good at failing can you learn to succeed more quickly.”

The Show Must Go On

“All women get hung up on perfectionism,” says Tanaka. “Every one of us lives our lives trying not to make a single mistake.” But in dancing, the tiniest mistakes are often overlooked in the big picture of the performance. Instead, dancers keep their heads high and smile on their faces, whether or not their feet miss a beat.

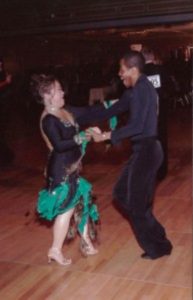

Tanaka’s first competition dance was a mambo—a highly-energetic Latin dance with complicated footwork. She felt good about her performance but agonized over a few missteps to her coach and dancing partner. “I thought there’s no way I could win with what I felt were such glaring mistakes,” she recalls, but was floored to be called to the judges table to receive her prize. “I was still pissed,” she says, but her coach assured her: the world of competitive dancing isn’t a world of minutae. She won, he told her later, because she danced full-out and smiled and looked like she was having fun. “Which,” she admits, “I was.”